Normal Extensions

A/B Testing: Stopping Time Bias

Avoid Biased Stopping Times

When you run an A/B test, you should avoid stopping the experiment as soon as the results “look” significant. Using a stopping time that is dependent upon the results of the experiment can inflate your false-positive rate substantially.

To understand why this is so, let’s look at a simpler experimental problem. Let’s say that we have a coin in front of us, and we want to know whether it’s biased – whether it lands heads-up with probability other than \(50\%\). If we flip the coin \(n\) times and it lands heads-up on \(k\) of them, then we know that the posterior distribution for the coin’s bias is \(p \sim Beta(k+1, n-k+1)\). So if we do this and \(0.5\) isn’t within a \(95\%\) credible interval for \(p\), then we would conclude that the coin is biased with p-value \(<= 0.05\). This is all fine as long as the number of flips we perform, \(n\), doesn’t depend on the results of the previous flips. If we do that, then we bias the experiment to favor extremal outcomes.

Let’s clarify this simulating these two experimental procedures in code.

- Unbiased Procedure: We flip the coin 1000 times. Let \(k\) be the number of times that the coin landed heads-up. After all 1000 flips, we look at the \(p \sim Beta(k+1, 1000-k+1)\) distribution. If 0.5 lies outside a the 95% credible interval for \(p\), then we conclude that \(p\neq 0.5\); if 0.5 does lie within the 95% credible interval, then we’re not sure – we don’t reject the idea that \(p = 0.5\).

- Biased Procedure. We start flipping the coin. For each \(n\) with \(1 < n \leq 1000\), let \(k_n\) be the number of times the coin lands heads-up after the first \(n\) flips. After each flip, we look at the distribution \(p \sim Beta(k_n+1, n-k_n+1)\). If 0.5 lies outside a the 95% credible interval for \(p\), then we immediately halt the experiment and conclude that \(p\neq 0.5\); if 0.5 does lie within the 95% credible interval, we continue flipping. If we make it to \(1000\) flips, we stop completely and follow the unbiased procedure.

How many false positives do you think that the Biased Procedure will produce? We chose our p-value, \(0.05\), so that the false positive rate would be about \(5\%\). Let’s repeat each procedure 1000 times, assuming that the coin really is fair, and see what the false positive rates really are:

def biased_procedure(n):

false_positives = 0

for experiment_iteration in range(n):

successes = (np.random.random(size=1000) > 0.5).cumsum()

trials = np.arange(1, 1001)

cdf50_history = scipy.stats.beta(successes+1, trials-successes+1).cdf(0.5)

if (cdf50_history >= 0.975).any() or (cdf50_history <= 0.025).any():

false_positives += 1

return (1.0*false_positives)/n

def unbiased_procedure(n):

false_positives = 0

for experiment_iteration in range(n):

successes = (np.random.random(size=1000) > 0.5).cumsum()

trials = np.arange(1, 1001)

cdf50_history = scipy.stats.beta(successes+1, trials-successes+1).cdf(0.5)

if cdf50_history[-1] >= 0.975 or cdf50_history[-1] <= 0.025:

false_positives += 1

return (1.0*false_positives)/n

And when we try this out, simulating 10k experiments under each procedure:

In [64]: unbiased_procedure(10000)

Out[64]: 0.0526

In [65]: biased_procedure(10000)

Out[65]: 0.4912

Almost half of the experiments under the biased procedure produced a false positive. Conversely, \(5.26\%\) of the unbiased procedure experiments resulted in a false positive – which is close to the \(5\%\) false positive rate the we expected, given our p-value.

Practical Solutions

The easiest way to avoid this problem is to choose a stopping time that’s independent of the test results. You could, for example, decide in advance to run the test for exactly two weeks, no matter the results you observe during the test’s tenure. Or you could decide to run the test until each bucket has received more than \(10,000\) visitors, again ignoring the test results until that condition is met.

When you can afford to wait, I strongly recommend doing this. Setting a results-independent stopping time is the easiest and most reliable way to avoid biased stopping times.

Very, very rarely, doing this may require some steel-jawed stoicism; it’s hard to continue an A/B test when A’s empirical conversion rate is half of B’s, and you feel like you’re burning money every day that the test continues. In those cases, it would be nice if there were some way to stop the test early when the results are extreme.

It’s somewhat possible to do this, but one has to be careful. Let’s return to the coin example above. Let’s again assume that it’s fair: For each \(n\), what’s the right p-value to ensure that when we evaluate the test after “peeking” after the first \(n\) results come in, our false positive rate stays at \(5\%\)? Let’s find out empirically for a few values of \(n\):

def find_p_value(n):

flips = np.random.binomial(1, 0.5, size=(n, 100000))

successes = flips.cumsum(axis=0)

trials = np.ones((n, 100000)).cumsum(axis=0)

cdf_values = scipy.stats.beta(successes+1, trials-successes+1).cdf(0.5)

maxes = np.maximum.accumulate(cdf_values, axis=0)

p_values = mstats.mquantiles(maxes, [0.975], axis=1)

# Using symmetry

return 2*(1 - p_values)

We can plot this:

As we can see, the value goes to zero very quickly; this makes sense, since our risk of a false positive is only increasing as we flip the coin more, assuming that we peek after every flip and stop as soon as the result “looks significant”.

What happens if we only start peeking at some point? E.g., we flip the coin \(50\) times before looking, but for flips \(51, 52, \ldots, 100\), we stop as soon as the results look significant. We can also compute this empirically, and in fact the code is very similar:

def find_p_value_again(n):

flips = np.random.binomial(1, 0.5, size=(n, 100000))

successes = flips.cumsum(axis=0)

trials = np.ones((n, 100000)).cumsum(axis=0)

cdf_values = scipy.stats.beta(successes+1, trials-successes+1).cdf(0.5)

maxes = np.maximum.accumulate(cdf_values[::-1], axis=0)[::-1]

p_values = mstats.mquantiles(maxes, [0.975], axis=1)

# Using symmetry

return 2*(1 - p_values)

And here’s what that plot looks like:

We can translate these dynamic p-values back into the distributions that they came from in order to get a hard-and-fast boundary for stopping the test:

running_p_values = find_p_value_again(100)

distro = scipy.stats.binom(np.arange(1, 101), 0.5)

upper_bound = distro.isf(running_p_values/2).diagonal()/np.arange(1, 101)

lower_bound = distro.isf(1 - running_p_values/2).diagonal()/np.arange(1, 101)

plt.fill_between(np.arange(1, 101), lower_bound, upper_bound, alpha=0.5, linewidth=1)

This tells us, e.g., that if we peek at the experiment after 40 flips and want to know if the results are bad enough to stop the experiment, the answer is “yes” if fewer than \(\approx 30\% = 12\) of the flips landed heads up, and is “no” otherwise. (The graph should be ignored for \(n \leq 8\), since it isn’t even possible to arrive outside the bounds before then.) Something I want to stress is that we are not simply computing the naive \(95\%\) credible intervals after each flip; we are being much more stringent. Indeed, \(\mathbb{P}(Bin(40, 0.5) \leq 12) \approx 0.0083\).

One can easily re-use this idea in the context of an A/B test; instead of the simple model for flipping a coin, you’d use whatever posterior model you have for your experiment, and instead of the null hypothesis being that the coin is unbiased, it would be that each variant’s true rate is really no better than the control’s.

Two Notes

One: In the above, it would be theoretically better if we didn’t have a fixed null hypothesis for the coin’s true value (namely \(0.5\)), but instead used a prior distribution. In practice, I never do this. I sleep at night by reminding myself that stopping early is a questionable practice in the first place, the whole point of this exercise is to find a rough estimate of an acceptable stopping in the rare cases in which one variant is so bad that the experiment needs to be killed.

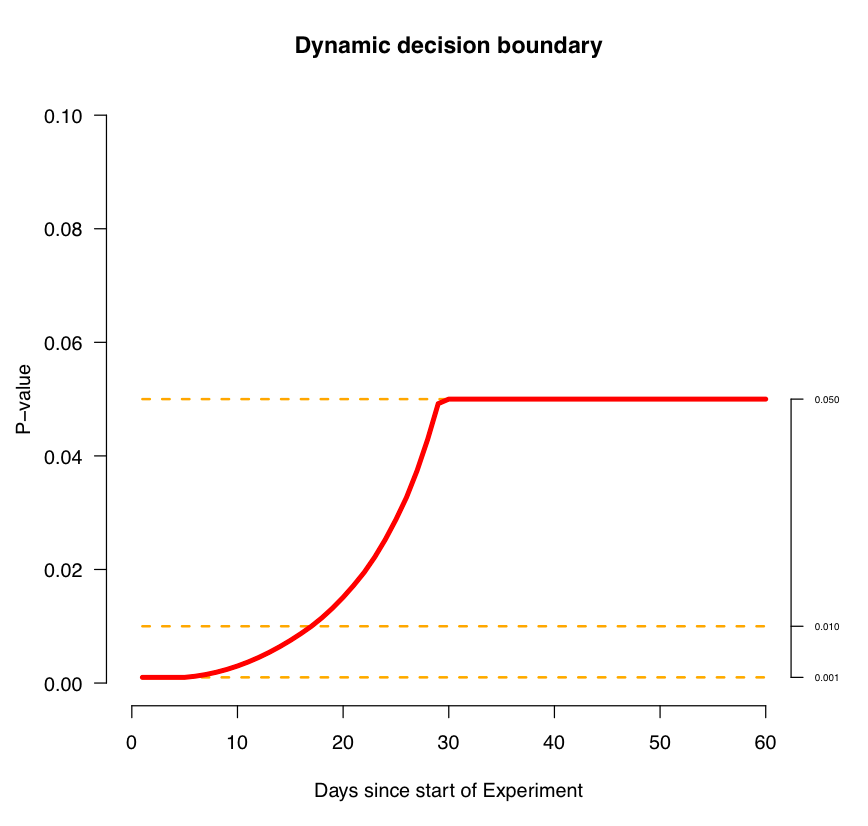

Two: Airbnb has a great article on the biased stopping time problem, and you should definitely check it out. As a nitpick, I disagree with this diagram:

In reality, the p-value never plateaus like that. (If you run an A/A test forever unless you hit a certain fixed p-value, you’ll eventually get a false positive with probability \(100\%\). Similarly, if you peek constantly and you set a flat p-value, you inexorably increase your false positive rate.) I think that this is a misstatement rather than a mistake; judging from the rest of the article, what’s probably meant is that they run experiments for no more than 30 days (or some other fixed value tied to sample size), and decide whether a significan effect exists at that point using \(p = 0.05\) (as we did above, deciding to stop and evaluate when the number of flips reached \(100\) if we hadn’t already squealed by then). Anyway, the article is great, and you should definitely read it!